Hangnail or heart attack?

How to navigate online health info

Three out of four web users say they search for health information online, according to Pew Research. But how can you know if that info is reliable? Anyone can publish a website, and it’s common for online health information to come with another agenda. Want to get rid of belly fat by eating only pomegranates? Or maybe cure your fatigue with this pill that you can only get from this doctor? Just click here!

Even popular sources can be suspect. WebMD exists in the first place to make money from advertising, not to fix your ingrown toenail. Recently, researchers found that half of Dr. Oz’s medical advice is baseless or flat-out wrong. More than half the students who responded to a recent Student Health 101 survey said they question the reliability of a health source at least twice a week.

In honor of National Healthcare Decisions Day (April 16), learn what to look for in a health website, and how to recognize red flags. These tips will help you sort the best from the bogus.

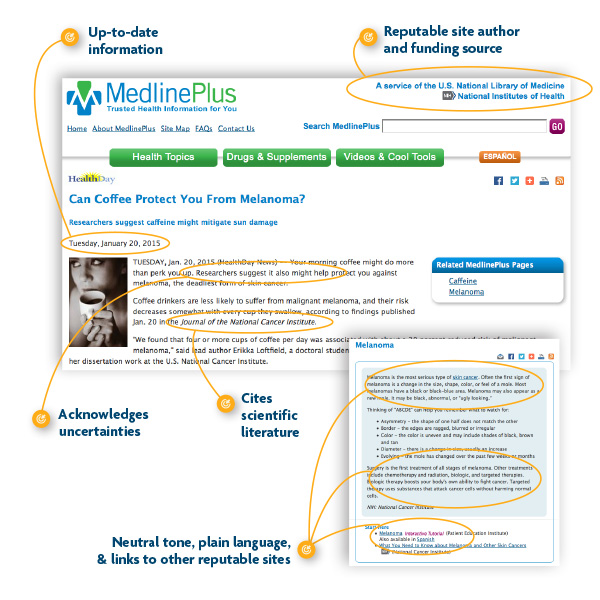

Up-to-date information

- All or most of the content has been created within the past five years.

- Some sites reference older information. This is OK if they are referencing a landmark finding or providing context for a newer study.

- The date the content was most recently updated may be provided at the bottom of the page. Not all websites have dates. If the source is reputable, this is OK.

Cites scientific literature

- Medical facts are cited and sourced in footnotes or on a sources page.

- The content is based on published, peer-reviewed studies by researchers affiliated with universities or other respected institutions, such as NIH. Be wary of research sponsored by an organization that has an interest in the outcome: e.g., a study on soda and obesity sponsored by the soft drinks industry.

- Ideally, the content is based on a meta-analysis or systematic review. These analyze data from many studies on the same topic. Meta-analyses are much more comprehensive and broadly applicable than any individual study. The Cochrane Collaboration provides systematic reviews.

- The content references studies from a range of sources. If 3 out of 5 sources are the work of the same researcher, tread carefully.

- The research cited involved a large number of human participants. If the findings were based on a dozen mice, forget it.

Acknowledges uncertainties

- Acknowledges when research is incomplete or conflicting. Unbalanced articles are often trying to sell a product or belief.

- Does not assume correlation equals causation. For example, this graph (link below) shows that the divorce rate in Maine decreased at roughly the same rate as the consumption of margarine. This doesn’t mean that margarine consumption drives divorce or vice versa.

- Divorce and margarine consumption: correlation =/= causation.

Reputable site author and funding source

- Reliable sources include government departments, such as NIH; universities; and certain evidence-based journals (e.g., Science).

- There are no obvious conflicts of interest involving the author(s) or the organization that sponsored the research. If the author is a lobbyist in Washington DC, it’s all over.

- To get a better sense of the source, click on About Us or the equivalent web page.

Neutral tone

- No talk of “Miracle cure!” or “Breakthrough!” Science usually advances in small increments. A single study rarely changes everything.

- “Miracle cures” and so on are usually a sales pitch. Don’t fall for it. Exclamation marks or price tags.

Plain language

- Trustworthy language is not overly technical. But it shouldn’t be “dumbed down” to the point where it’s not accurate anymore. If they’re trying to blind you with science, keep your eyes wide open.

Links to other reputable sites

- Links should not be to pages asking you to buy something.

- Many reputable sites will not link to other pages at all.